In 1780, New Jersey was the beating heart of a war for independence. A tragic murder stirred the people. Road ways that today carry commuters and shoppers once thundered with marching boots, rumbling artillery, and the whispered codes of spies. The Forgotten Victory Trail follows this history—connecting key towns and landmarks through a forgotten story of taverns, pulpits, Masonic halls, and rebel networks that shaped the fate of a nation.

It began with whispers, long before the first musket fired. In the taverns of Elizabeth and the parsonages of the New Light, word spread that the King’s officers were not merely at war with the rebel army — they were hunting its soul. Reverend James Caldwell, the “Rebel High Priest,” was on a list, his sermons marked as dangerous as any rifle shot.

Across the water, Staten Island was crawling with redcoats, Hessian bayonets glinting in the morning haze, but more dangerous still were the Loyalist agents — men born in New Jersey, now wearing the King’s colors, slipping through the marshes with orders in their pockets. Some came not for the forts or the farms, but for a handful of names. Kill the leaders, burn the churches, scatter the people — and the rebellion would die.

By June 1780, the plan was in motion. Two great strikes were ordered — one at Connecticut Farms, another at Springfield. The British landed at Elizabeth Point, their columns moving like a slow tide inland, but before they could reach their prize, the hills came alive. Minutemen poured out to the Watchung cliffs, boots pounding the summer roads, muskets at the ready. These were no parade soldiers — these were farmers and millers, men with smoke still on their shirts from the morning hearth, now marching to hold the line.

They took the streets, barricading lanes with overturned wagons and broken fences, firing from doorways and churchyards. Maxwell’s Brigade, hardened from Monmouth and winter camps, anchored the fight — but it was the militia, the young and the old, who turned the advance into a crawl. Even Washington said they fought with valor. Still, the shadow war pressed in. Loyalist guides pointed the British to homes marked for destruction. The Old Academy — cradle of abolitionist thought — was set alight. The parsonage at Connecticut Farms burned with Hannah Caldwell dead, and yet, as smoke rose over the town, more rebels arrived over the ridge, their ranks swelling with every mile.

By Springfield, the streets were a fortress. The King’s men, who thought they would march unopposed to Newark and beyond, found themselves surrounded by fire from the houses, from the mills, from the very ground they marched upon. The conspirators’ plan — to kill the rebellion in one blow — collapsed in the face of a people who would not yield. When the redcoats finally fell back toward Elizabeth Point, they left behind only ash and the echo of boots — the Minutemen still holding the hills, still owning the streets. The King’s authority might have still ruled the seas, but in New Jersey, the streets belonged to the people.

This is where the trail begins on the east, on the front lines, the heart of New Jersey, facing occupied New York. Springfield and Connecticut Farms (Union), sit between Washington’s Army up the mountains, and the British fleet in Occupied New York across the water. New Jersey—the Cockpit of the American Revolution—witnessed more battles than any other state, hosted Washington longer than any other place, and was the stage for some of his most decisive victories.

Okay, get your horse ready… Riding the Forgotten Victory Trail

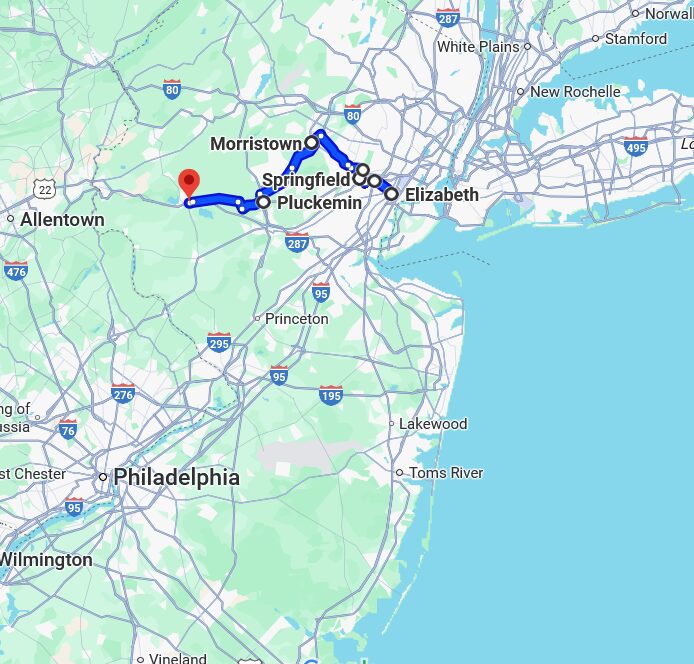

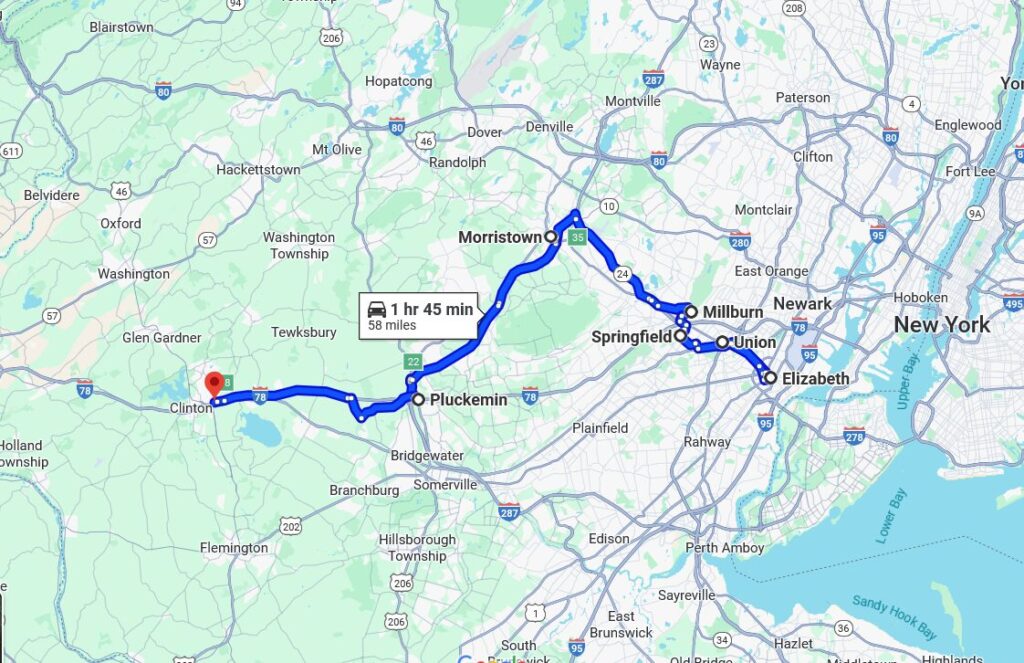

As you scroll down this page, you’re following a once-forgotten route stretching across the heart of New Jersey—site by site, from east to west—just as riders, messengers, and soldiers once did. Each stop is mapped with the distance shown for a modern cyclist, so you can imagine the pace of traveling the trail today.

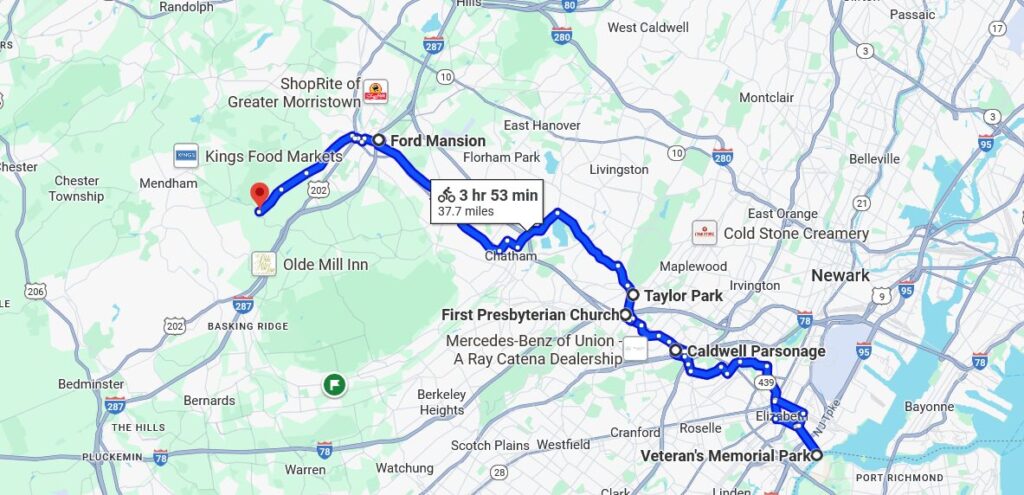

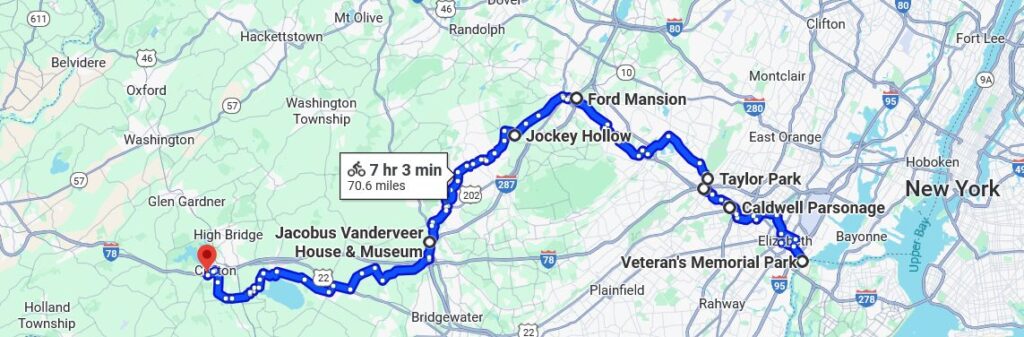

We begin in Elizabeth, at Veterans Memorial Park, where British forces twice landed in 1780. The route then moves to Union (Connecticut Farms) and the Caldwell Parsonage, scene of Hannah Caldwell’s tragic murder. From there to Springfield and it rises to Taylor Park in Millburn, where the Forgotten Victory Trail’s first historical marker stands at the ground the soldiers marched across to defend the Rahway River crossings into town.

The trail then reaches Morristown, Washington’s headquarters during the brutal winter of 1779–1780. The Ford House—where Washington stayed until his last recorded day there, June 23, 1780—anchors this section, paired with the sprawling encampment at Jockey Hollow, where thousands of soldiers endured and later fought in the 1780 battles. Further west lies Pluckemin, home to the Continental Army’s first artillery academy, commanded by General Henry Knox, whose headquarters stood at the Vanderveer House.

Beyond was the wilderness of colonial New Jersey, where the Swift Stage Coach shuttled travelers between New York and the nation’s then-capital in Pennsylvania. In Clinton, the historic Bonnell Tavern—once nearly lost—is set to shine again as a beacon along the trail, a place where travelers today can pause just as generals and soldiers once did.

This is a New Jersey story told through every step of the route—one that includes forgotten voices from all sides and backgrounds. It’s a living history of Rebel Reverends, Black soldiers, Women of courage, sharpshooting Militiamen, and a United People of many faiths and colors—bound by an idea: a United America.

For context: an average cyclist rides about 12–15 mph, while a good Revolutionary-era courier on horseback could cover 7–10 mph at a steady trot, with bursts of 15–20 mph at a gallop—but only for short stretches before resting the horse. In other words, today’s rider might match or even beat the pace of a mounted messenger over long distances, but in 1780, those horses were carrying far more than a rider—they carried urgent news, supplies, orders, and the fate of towns in their saddlebags.

1780- A Year on the Brink

By the spring of 1780, the American cause in New Jersey was hanging by a thread. The previous winter had been the harshest in living memory—freezing even the saltwater harbors and trapping supplies far from the hungry soldiers in Morristown’s encampments. Food was scarce, clothing threadbare, and pay long overdue. Grumbling in the ranks grew louder as men thought of their untended farms and spring planting.

The British saw an opportunity and struck at the very heart of the rebellion’s stability—not only on the battlefield but in the economy. Counterfeit Continental currency, printed in New York under British supervision, flooded the colonies, destroying faith in the fledgling nation’s money. Every loaf of bread, every musket ball, became harder to afford with that kind of manipulation.

For the American ‘Rebels’ of 1780, this was more than political struggle—it was life or death. The Declaration of Independence was now a signed challenge to the Crown, and the enemy knew that if they could crush New Jersey’s resistance, they could choke Washington’s army into submission. The skies turned black one day in “The Dark Day of May 1780”- it was an omen of something horrible on the rise. Many soldiers were at the end of their service and numbers were down, morale was low, people were suffering and not knowing if revolting would be the end of everything.

Even then, a spark of light admonished souls. The Good Reverend Caldwell- the rebel reverend who served his people, the people who built a free state and a new nation- it is his story and he above all has been forgotten. He helped build militia regiments, feed the army at Jockey Hollow, and even served as an early State Senator, cutting away the Loyalist network in New Jersey, until he was assassinated November 24, 1781 at Elizabeth Point.

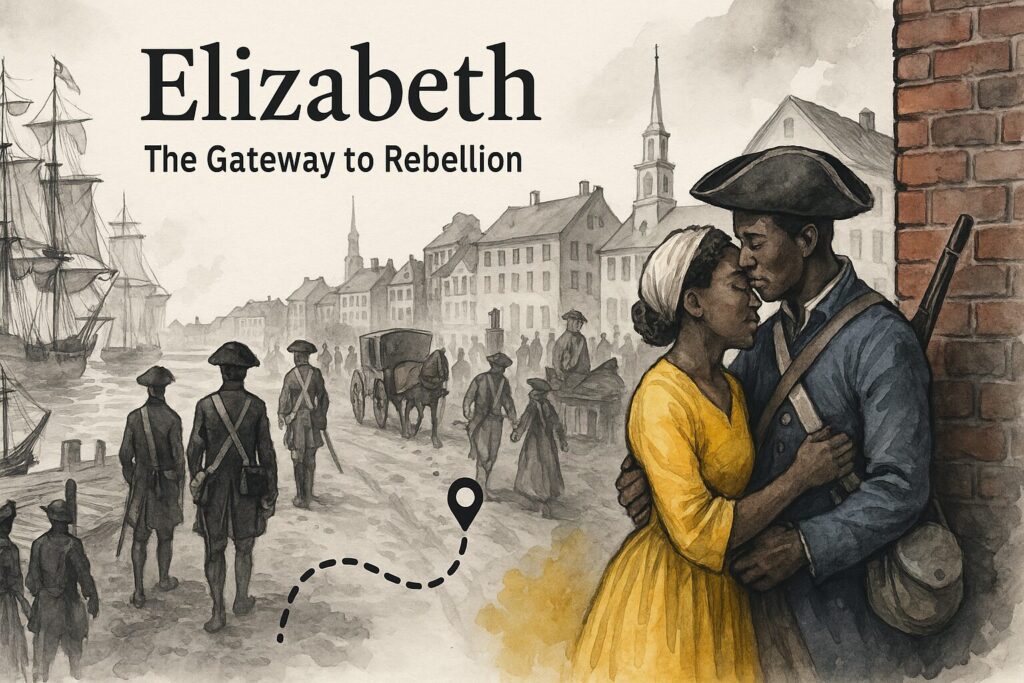

Elizabeth

(1) Elizabeth – The Gateway to Rebellion

Elizabeth was no quiet colonial port—it was a crucible of Revolutionary defiance. From Boxwood Hall, Elias Boudinot and fellow Sons of Liberty plotted resistance, while the Old Academy stood as a beacon of learning and abolitionist thought, training minds to challenge both the Crown and its engine of oppression—the Duke of York’s Royal African Company, powerbroker of the transatlantic slave trade. Inns like the Red Lion rang with fiery debates, and the “New Light” Presbyterian pulpit of Reverend James Caldwell thundered against tyranny and royal corruption. For Anglicans, the King was God’s anointed; for Presbyterians, God alone ruled over man. This spiritual divide placed Caldwell squarely in the crosshairs of Loyalist clergy and royal authority.

Across the Kill Van Kull lay British-occupied Staten Island, held since 1776. Even there, Loyalist homes were sometimes plundered by British officers, for the Royalists did not always see New World Loyalists as equals. The British plundered New Jersey—records tell of women assaulted, livestock stolen, family Bibles taken, and homes reduced to ash. Loyalists were often neighbors of those they called “rebels,” and the war split families—such as William Franklin, the last Royal Governor of New Jersey, and his father, Benjamin Franklin. Some sons marched in red coats, others in the Jersey Blues.

Just as the Crown dismissed Loyalists as lesser subjects, it also later denied equality to Black men—yet many stepped forward willingly to fight for a freedom still only promised in words. Heroes like Oliver Cromwell and William Stives freely took up arms for an idea of liberty not yet secured for all. Others, like Cudjo Banquante, stood in defiance of a world still bound in chains. At the Battle of Monmouth in 1778, Cudjo fought under Brigadier General William Maxwell—who would later defend Springfield—alongside Cromwell and Stives. That day, more than 800 Black soldiers stood with the Continental Army. Together they guarded Elizabethtown Point in 1778, held Paulus Hook (now Jersey City) in 1779, marched on the Sullivan Expedition into Pennsylvania and western New York, and fought in the final victory at Yorktown in 1781. Cromwell and Stives both received the Badge of Merit—the “Purple Heart”—from General George Washington himself, a testament to their loyalty, bravery, and valor. These men, some born into slavery and others born free, carried the cause of liberty not only on their shoulders, but in the spirit of the “New Light” movement, for which they fought for a freedom the young nation had not yet promised them—but one they believed must come. Their very service was a defiance to a royal system that had long enriched itself on human slavery. Ironically, slavery later became a weapon used by the British against the very colonial order they had built in the New World. Many Black soldiers in Royalist ranks were promised freedom under proclamations such as Lord Dunmore’s (1775) and Sir Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation (1779). At war’s end, thousands were evacuated to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and other parts of Canada as “Black Loyalists,” but not all remained free—racial prejudice, broken promises, and economic hardship forced some into indentured servitude, re-enslavement, or even abduction back into slavery.

The Old Academy next to the Presbyterian church, was where Alexander Hamilton went to school alongside Aaron Burr and others. The academy taught from ancient books, many lost wisdom, which the crown did not want taught. It became a beacon of thought, which is why it and it’s satellite academy in Newark, were burned first in 1779 and again in January 25, 1780. The Old Academy, built in 1771, served as both a school and a meeting place for Patriot leaders. Because it was associated with Presbyterian “New Light” rebels — and was seen as a hub of anti-British, abolitionist thought — it became a target.

In January 1780 during the harsh “Hard Winter,” British and Loyalist forces crossed from Staten Island, struck Elizabeth, and burned several buildings, including the Old Academy and Rev. Caldwell’s home. Many repeated raids devastated the town’s infrastructure and left it as a no-mans-land with burnt buildings and remnants of war. They weren’t just military strikes — it was part of the larger British effort to break Presbyterian influence in New Jersey, which is why Reverend Caldwell became a primary target in the spiritual war at the pulpit. His congregation were made up of the leading citizens of New Jersey from William Livingston the ‘rebel’ Governor and others. His church was open to all faiths and all people, which became a problem for some, like the Anglican Church of England who take an oath that the King is a representation of God among men, with the problem of corruption at an imperial scale no matter the cost to people or land.

In 1780, Elizabeth became the flashpoint for British and Loyalist incursions. From here, their columns pushed toward Springfield, burning homes and sowing terror. The blood of martyrs and the spark of liberty both flowed in these streets. British and Hessian forces landed at Elizabeth Point—the end of First Avenue (now Elizabeth Avenue)—on June 7 and again on June 23, and it was here, in 1781, that Reverend Caldwell—the “Rebel High Priest” —was assassinated by a bribed Loyalist turncoat.

By December 1780, Caldwell had been appointed a legislative Senator of New Jersey, serving alongside his friend and fellow militia captain from Somerset, Frederick Frelinghuysen. Together they wielded statewide influence, working to dismantle the entrenched Royalist networks that still lingered in New Jersey and New York. His efforts might have reshaped America’s course even earlier, had they not been cut short when—like Hannah before him—he fell to two bullets. Caldwell’s death extinguished one of the rarest lights in our history, a man whose passion transcended politics and creed, seeking the betterment of all. Those shots were meant not only to end a life, but to shatter the spirit of a free and equal America, unbound by any ruling hand.

Here in Elizabeth is where the story begins—and where it ends.

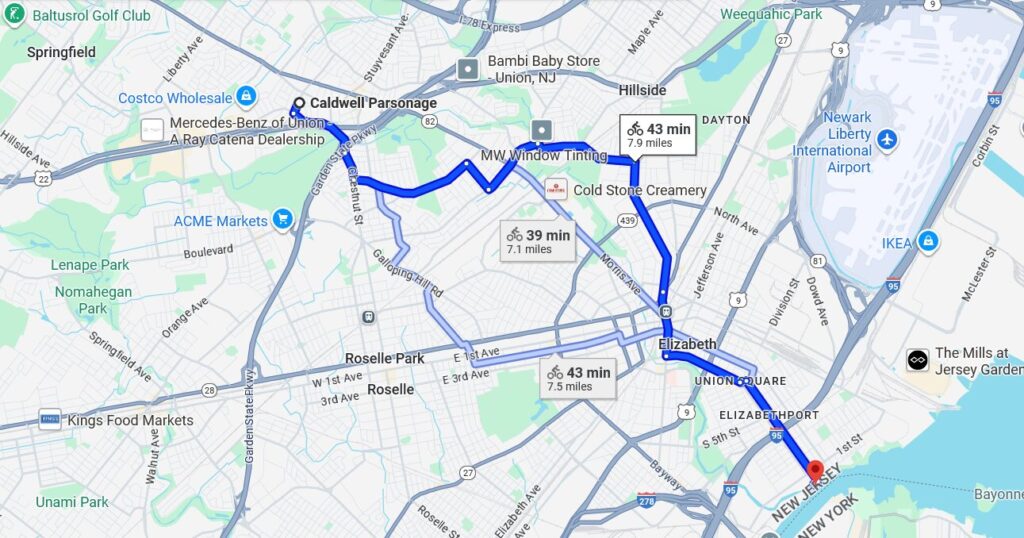

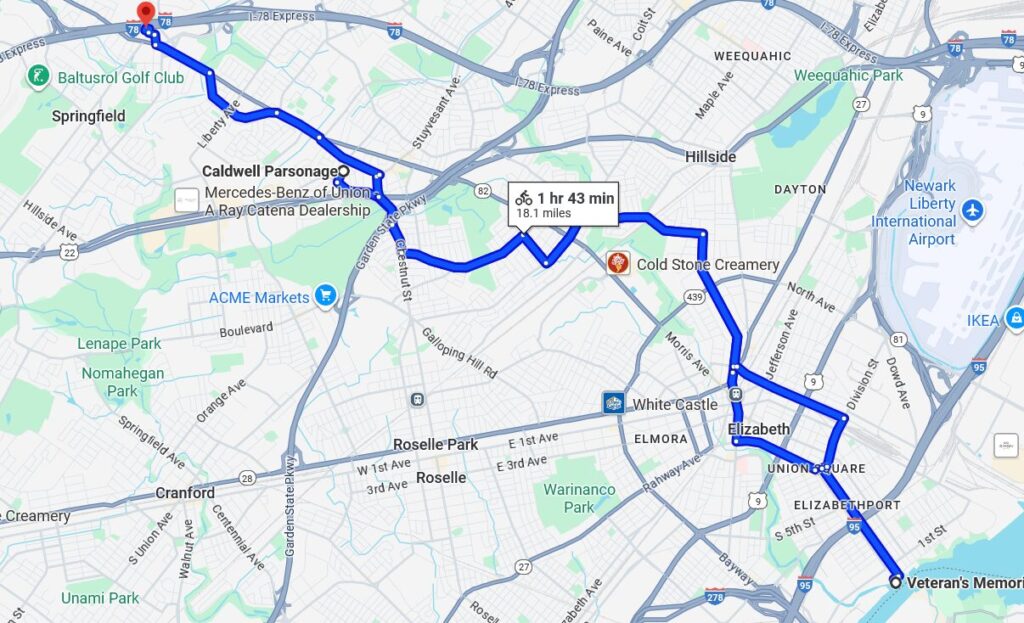

Forgotten Victory Trail- starting at (1) Elizabeth Point to (2) the Caldwell Parsonage in Union

Connecticut Farms (Union)

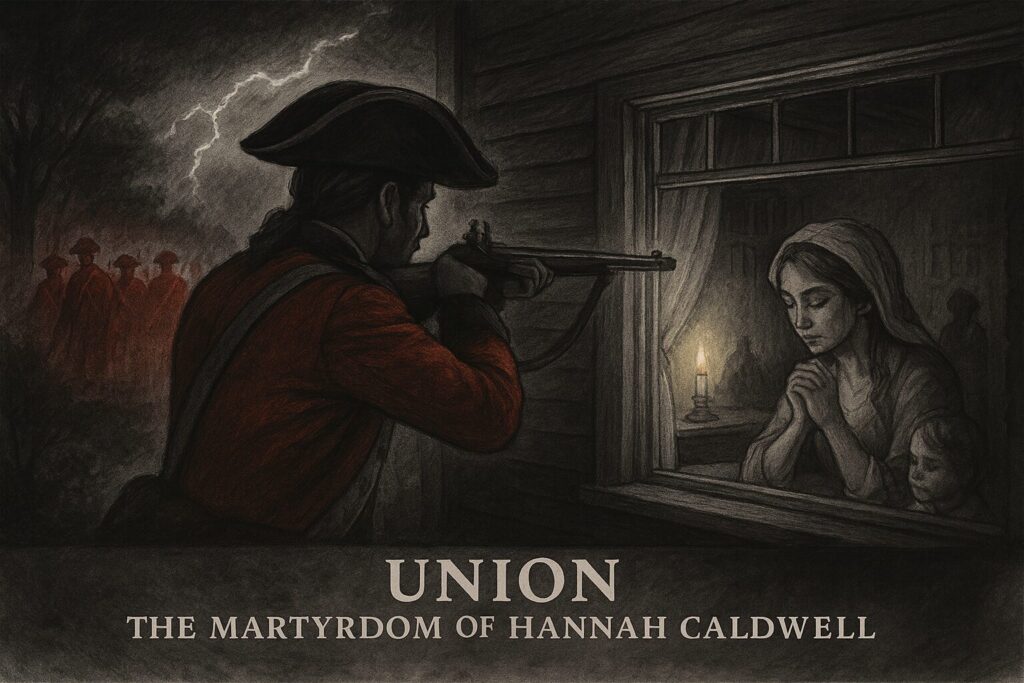

(2) Union – Striking at the Rebel Heart – The Martyrdom of Hannah Caldwell

Union’s place in Revolutionary memory is marked by tragedy. On June 7, 1780, Hannah Caldwell, wife of Reverend James Caldwell, was shot and killed in her own home during the Battle of Connecticut Farms. Her death was a calculated blow—an act meant to silence a rebel preacher whose sermons had become rallying cries for independence. Evidence to this has been rarely brought up despite two investigations and multiple signed testimonies of the event, never used, in favor of only the British propaganda from the New York Gazette. Union’s Presbyterian church, a center for the so-called “Presbyterian Rebellion,” was burned by British forces. This was not just military maneuvering—it was an attack on the moral backbone of the rebellion. The reverend moved to Union after the British forces burned his home and church in Elizabethtown.

In the summer of 1780, the Royalist high command in New York met at Fraunces Tavern—not to toast victory, but to plan an “experiment” on New Jersey. The goal was not merely to defeat American forces in the field, but to shatter the spiritual core of the Jersey Rebellion. They knew its heart beat in the Presbyterian pulpits, and none thundered louder than that of Reverend James Caldwell. If they could silence him, they might still strangle the rebellion’s will.

The plot was chilling in its precision: send an assassin to eliminate Caldwell, and if the preacher could not be reached, his wife would do. Break the man’s heart, break the pulpit, and you break the people. Hannah Caldwell, a beloved mother of nine, sat motionless in prayer with two other women and several of her children, the quiet moment shattered when she became the chosen substitute target. On June 7, 1780, as British and Loyalist troops clashed with militia in the Battle of Connecticut Farms, a Red Coat jumped the fence and approached the window very closely and an explosion rang through the parsonage window. Hannah fell dead where she stood. Two bullets for close assassinations, hit her right in the chest, killing her instantly.

This was no stray bullet—it was the calculated work of a Royalist faction inside the British ranks. The conspiracy’s architects were men like William Tryon and William Franklin, both former royal governors stripped of power by the rebellion. Tryon, notorious for burning Connecticut towns and ordering civilian massacres, brought with him Lt. Col. John Simcoe of the Queen’s Rangers—a commander with a blood-soaked record, from raiding New Jersey farmsteads to murdering sleeping Quaker boys at a Salem boathouse. These were leaders who saw brutality as a tool, not a crime.

Union’s church—Caldwell’s pulpit—was burned to the ground, its library of over 500 volumes stolen. Among them were works on theology, law, natural philosophy, history, and the political treatises that had armed Caldwell’s sermons with fire. His library was more than books—it was a bundle of ideas. The theft was as symbolic as it was practical: to rob the preacher of his arsenal of words.

Around them, the invisible war of spies swirled. Washington’s agents slipped between Elizabeth, Staten Island, and New York, shadowed by the Loyalist intelligence network under Tryon and Franklin. These were not just opposing armies, but opposing secret societies, with taverns, inns, and back rooms serving as both war councils and intelligence posts. Yet despite smaller numbers, local militia and Continentals held their ground. Union, Springfield, and the surrounding villages formed the narrow shield that guarded the road to Morristown—Washington’s headquarters and the nerve center of the Revolution.

During the climactic Battle of Springfield, Washington, Lafayette, and Caldwell himself stood on the heights above the town—today’s South Mountain in Millburn—watching the smoke and flashes of musket fire below. They saw the first flames rise, not yet realizing it was Caldwell’s parsonage burning. By nightfall, the British retreat became a nightmare. A massive summer storm rolled in, lightning splitting the sky, rain turning roads to rivers. Men were lost in the blackness, drowned in flooded streams, or left behind in the chaos. Lightning illuminated the dead lying in ditches and along the road back to Elizabethtown—a grim reminder that even in defeat, the British had left their mark in fire and blood.

It was an act of darkness meant to snuff out the light of the Jersey Rebellion, and yet, somehow, the pulpit would speak again.

Springfield

(3) Springfield – Holding the Line

Two weeks after the bloodshed at Connecticut Farms, the war came roaring back to New Jersey’s heartland. On June 23, 1780, Springfield became the stage for a fight that would decide whether Washington’s army could survive the summer. British and Hessian forces—nearly 5,000 strong—marched from Elizabethtown intent on smashing through the New Jersey militia and Continental Army, then pushing on to Morristown to strike at the commander-in-chief himself.

General Nathanael Greene, commanding in Washington’s absence, deployed a patchwork force: veteran Continentals, ragged militiamen from Essex, Union, and Morris counties, Somerset, Hunterdon and even teenage recruits barely trained to fire a musket. Their task was simple to say but deadly to carry out—hold the bridges over the Rahway River long enough to block the enemy advance.

The fighting was fierce and intimate. Hessian bayonets clashed with local muskets along Vauxhall Road and at the Galloping Hill bridge. From the pulpit of his soon to be destroyed Springfield church, Reverend James Caldwell emerged, bringing Isaac Watts hymnals. He tore them apart and handed the pages to soldiers for musket wadding—turning sacred verse into instruments of resistance. “Put Watts into them, boys!” became the battle cry of the day.

By afternoon, Greene’s forces had forced the British back across the Rahway. Frustrated, the enemy vented their rage by burning Springfield to the ground—homes, mills, and shops reduced to ash. Only four buildings survived, spared by sheer chance. But though the town smoldered, the line had held. Greene and Washington were confused at why both Connecticut Farms and Springfield attacks occurred at all. There was no chance of easily making it up the hill to the Watchung mountains and over to Morristown. Greene admitted if it was purely to destroy the town it was a disgraceful act. Gen. Clinton had already left, leaving Kynphausen to create a scene for the British withdrawal. Vengeful Royalists and Loyalists were more than happy to torch the place under the Queens Rangers.

Springfield was more than a local defense—it was the last major British attempt to invade the interior of New Jersey. This stand preserved Morristown as Washington’s stronghold and kept the war’s momentum from swinging back to the Crown. For the farmers, merchants, and ministers who fought here, it was proof that New Jersey’s “Presbyterian Rebellion” would not be broken by fire or steel.

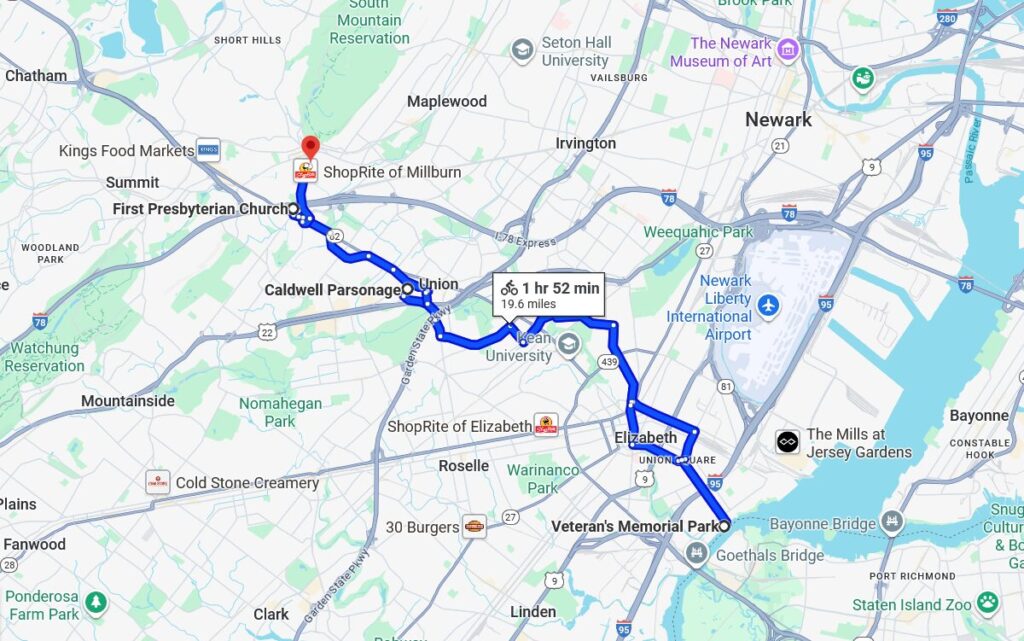

Forgotten Victory Trail- starting at (1) Elizabeth Point to (3) the Caldwell Presbyterian Church in Springfield

Millburn

(4) Millburn – The Rahway River Crossing

Millburn’s Taylor Park sits on land where the Rahway River once ran red with the struggle to slow the British and Hessian advance. ‘Rebel’ patriot forces here used the terrain—bridges, river bends, and wooded hills—to delay the enemy’s march from Millburn Ave to Vauxhall and Main Street toward Springfield. Two bridges forded the waterways, where intense battle took place.

Inns and farmhouses along the route served as impromptu headquarters, quarter master supply depots, and rallying points. Many of these were run by families whose loyalty to the cause cost them dearly. Rev. Caldwell used the ‘Vauxhall’ on 40 Main Street to supply the rebel army. Brison’s Inn, where today’s Middle School stands, just feet away from the Paper Mill Playhouse, is where tired soldiers fell for rest after the Battle of Springfield was over.

Two critical crossing points—nearly where Main Street now intersects the rail and Route 78 overpass—was ‘Old Main Street’ where the soldiers came from the Springfield battleground. The road would have let out and become what is today ‘Church Mall” beside Caldwell’s church. Inns and farmhouses lined the route transformed into impromptu command posts, supply depots, and rallying grounds. One such establishment—the Vauxhall inn at 40 Main Street—served as a vital quartermaster’s site supporting the rebel army. Nearby, at the spot where today’s Middle School stands just steps from the Paper Mill Playhouse, Brison’s Inn sheltered fatigued soldiers seeking rest after the Battle of Springfield.

Mounted among this tide of resistance was Samuel Beach of Newark, who hurried from the city to join the fight on June 23. Notably, Private Jacob Francis, a free Black man from Amwell Township, served in the Third Hunterdon County Regiment and stood with New Jersey militia that day. His service personified the statewide stream of men—like Abraham Bonnell and Samuel Quick and other militiamen—answering the call to defend the road to Morristown.

On June 23, 1780, amid the heat and chaos of the Battle of Springfield, Major General Charles “Light Horse Harry” Lee held firm at the Vauxhall Road crossing, reinforcing Vauxhall Bridge with a detachment of dismounted dragoons, small parties of militia, and a reinforcement of Colonel Matthias Ogden’s 1st New Jersey Regiment—some 179 men strong. Positioned just west of the bridge, Lee deployed his cavalry in echelon behind a nearby crossing known as “Littell’s Bridge,” allowing his men to deliver disciplined, concentrated fire along the road as Simcoe and the British and Loyalist forces advanced. Colonel Moses Littell, who commanded New Jersey militia at Vauxhall Bridge, is buried in the Millburn Cemetery, which forms part of the historic First Presbyterian Church burial ground. Littell and his men helped hold the bridge in concert with “Light Horse Harry” Lee’s cavalry and detachments of Continentals. These impromptu defenses, blending cavalry, infantry, and militia lines, slowed the enemy’s flank and bought critical time for General Greene’s forces in Springfield—helping to halt the British push toward Morristown.

In the thick of battle, militia and Continentals stopped the enemy’s advance—and even when the British burned Springfield, the line held. Yet this triumph on the field belied a more sinister design. General Greene and Washington, puzzled by the limited-engagement approach, later realized that the British incursion wasn’t intended as a full-scale conquest, but a strategic campaign of terror—designed to burn, to kill, and to cripple the spirit of resistance.

That was the true target: smash the towns, silence the pulpit, terrify the populace. Though the conspirators achieved destruction at Union and Springfield, they failed to extinguish the resolve of New Jersey spirit.

Forgotten Victory Trail- starting at (1) Elizabeth Point to (4) Vauxhall (Littell’s) Bridge in Millburn

Morristown

(5) Morristown – The Winter Encampment

Morristown was both fortress and lifeline for Washington’s army, and no places capture that dual role better than the Ford Mansion, Jockey Hollow, and the high crest of Fort Nonsense.

Samuel Ford Sr. fought in the first Battle of Springfield on December 17, 1776. Years later, his home would serve as Washington’s headquarters during the brutal winter encampment of 1779–1780. Washington paid rent to Mrs. Theodosia Ford during his stay, a rare courtesy to a civilian host. His last day in the Ford House coincided with the second Battle of Springfield—June 23, 1780—the final major British invasion into New Jersey.

From Fort Nonsense, soldiers could see the line of beacons stretching across the state, including one at the Hobart Gap. On June 7 and again on June 23, during the Battles of Connecticut Farms and Springfield, the sight of that beacon ablaze would have been an unmistakable call to arms. An express rider would have sped from the gap to Washington’s headquarters, summoning him, Lafayette, and Knox, among others, to take detachments toward the hills above Springfield. By the time they reached Connecticut Farms, the devastation was already plain—burned homes, ransacked farms, the acrid smell of smoke and death, and the shocking news of Hannah Caldwell’s murder.

Despite its dismissive name, Fort Nonsense was anything but pointless. Perched on the highest ground in Morristown, it commanded sweeping views over the surrounding valleys and ridgelines. In 1779, it became a key node in New Jersey’s beacon system—signal fires placed on elevated points to warn of enemy movements. From here, soldiers could spot the Hobart Gap beacon to the east, the flame cutting the darkness during both battles in June 1780. The system’s design was simple but brilliant: light the beacon, dispatch an express rider, and within hours militia could converge on threatened points like Vauxhall Bridge or the Rahway crossings. The irony of its name comes from local lore claiming Washington ordered its construction simply to keep idle troops occupied, yet in reality, its elevation made it one of the most critical early-warning posts in the state.

Jockey Hollow housed thousands of soldiers through the coldest winter of the century, their survival dependent on supply lines threading across Union, Springfield, Millburn and Hunterdon. Reverend James Caldwell, working from his own burned parish, helped keep those lines open and supported the installation of New Jersey’s beacon system—later stationed in 1779 by General William “Lord Stirling” Alexander. These beacons were the alarm bells of the Revolution, able to summon militia from miles away to reinforce points like Vauxhall Bridge or the Rahway crossings.

Some nights, the atmosphere was tense; other nights, more convivial, as officers shared a rare glass of wine before returning to their frozen huts at Jockey Hollow in the winter of 1779-80. Yet always, there was the hum of urgency—the awareness that just beyond these walls, the British still held New York, and the next movement of troops or flicker of a beacon could summon them all to saddle and march before dawn.

Inside the Ford House- Washington’s Headquarters

Step into the Ford House in May 1780, and you’d find the parlor transformed into a military nerve center. At the head table sat Washington, his demeanor calm but eyes always scanning the maps spread before him. Near the hearth, the young Marquis de Lafayette leaned forward in quiet discussion, while across the room Benedict Arnold, still wearing the uniform of a trusted general, listened with measured intensity. Their talk centered on the anticipated arrival of the French under Rochambeau—a potential turning point in the war.

Outside, sentries from the Commander-in-Chief’s Life Guards stood, a wind in the air as they watched over the approach roads. The household staff moved briskly in and out, among them William “Billy” Lee, Washington’s enslaved valet, tending to the General, his uniform and boots. Theodosia Ford, still grieving the loss of her husband Samuel, kept the house functioning under the strain of hosting an army’s command staff—meals for officers, quarters for aides, and endless requests from the general’s orderly book.

Morristown’s network—headquarters, encampment, and beacon—was more than a defensive cluster. It was the central nervous system of New Jersey’s Revolutionary resistance, and in June 1780, it proved that communication, coordination, and speed could hold the line against even the strongest foe.

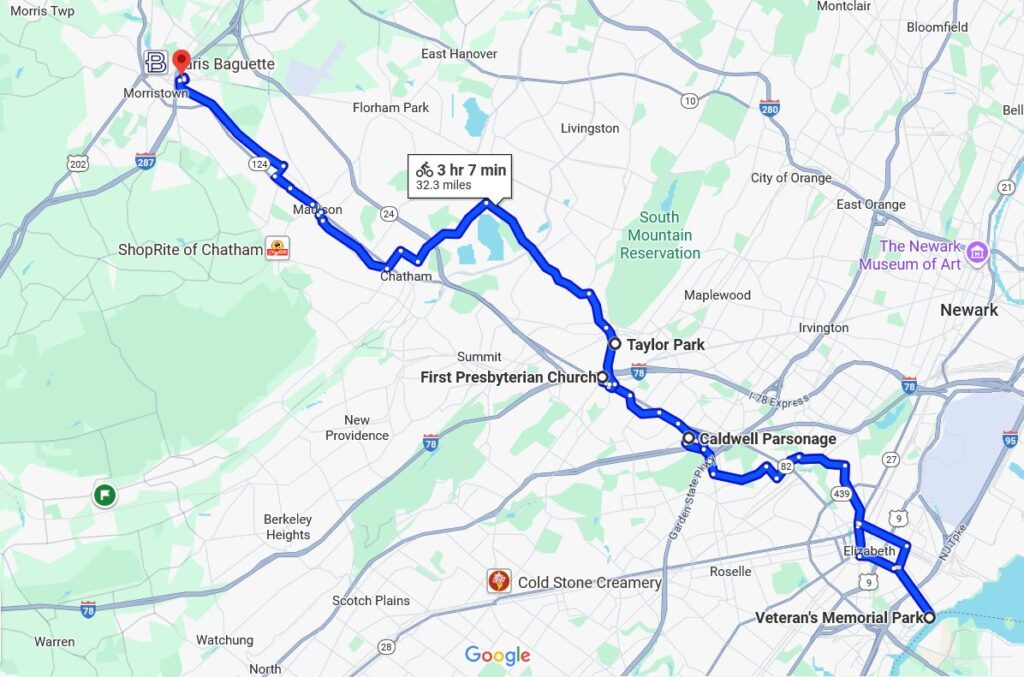

Forgotten Victory Trail- starting at (1) Elizabeth Point to (5) the Ford House (Washington’s HQ) in Morristown

Pluckemin

(6) Pluckemin – The Artillery Academy

In 1780 Knox would be with Lafayette and Washington, viewing the decimated ruins of Connecticut Farms in early June. Before the Morristown encampment, General Henry Knox led the Continental Army’s artillery training at the Pluckemin Artillery Cantonment—America’s first true military academy, serving as the intellectual and logistical heart of winter operations in 1778–79. Soldiers learned mathematics, engineering, and gunnery techniques necessary for efficient, mobile artillery—skills that would prove decisive in the 1780 campaigns, Artillery trained soldiers used these skills on the field in the Battle of Springfield. Even some militia trained at the camp, which ended up providing one of the only canons left on that fateful June day. The cantonment included barracks, workshops, and an academy structure, all laid out in a well-organized “E” formation encircling a parade ground.

Yet Pluckemin was more than a school of arms. On February 18, 1779, Knox and the artillery officers hosted a magnificent Grand Alliance Ball to commemorate the first anniversary of the American–French alliance. General Henry Knox and his wife, Lucy Knox hosted the event and were central figures of the evening. Over 400 people attended, including General Washington, Mrs. Washington, General Nathanael Greene and Mrs. Greene. Less than a year later, in January 1780, their son Nathanael “Nat” Ray Greene would be born—leaving open the charming possibility that the joy of that night extended far beyond its music and fireworks. The festivities were as elaborate as they were symbolic. Guests gathered in the cantonment’s academy building—an elegant, plastered room measuring roughly 50 by 30 feet, crowned with a cupola—illuminated by glowing candlelight and alive with music and conversation. A dinner followed by toasts and an allegorical backdrop adorned with thirteen arches captured the spirit of the alliance and American resolve. The evening concluded with fireworks that lit up the night sky—an eloquent, celebratory signal of solidarity between the young nation and its French allies.

Why It Matters on the Forgotten Victory Trail

Not only is America’s First Military Academy Forgotten, it’s not just a New Jersey story, but a ‘Forgotten Chapter‘ of the American Revolution and it all comes together in 1780. This ball was more than a social highlight—it was a statement. In the shadow of war’s hardship, it embodied unity, confidence, and hope. While gunners sharpened their skills by day, at night they built camaraderie in celebration of alliance. The training at Pluckemin forged the artillery officers who would later hold the line in New Jersey’s battles in 1780; the ball restored the spirit that sustained them.

Forgotten Victory Trail- starting at (1) Elizabeth Point to (6) the Gen. Knox Artillery Academy (America’s 1st) in Pluckemin

Clinton

(7) Clinton – The Western Supply Line

Clinton and the surrounding Hunterdon County countryside were critical to the war effort, serving as a western supply hub. Farmers, millers, and blacksmiths here fed and equipped the army. Taverns along the Delaware River provided safe meeting places for couriers and militia leaders.

Occupied by Colonel Abraham Bonnell in the late 1760s, the Bonnell Tavern in Clinton, New Jersey, quickly became the beating heart of Hunterdon County’s ‘Patriot ‘American’ cause. By 1770 it was the region’s meeting and voting place, and in August 1775 it witnessed the birth of the local minutemen under Charles Stewart—men who would march to New York in 1776 and later fight at Monmouth, Millstone, and Springfield. Bonnell himself served as Colonel of the county militia alongside Joseph Beavers, guiding his regiment through some of the war’s fiercest campaigns. Long after the Revolution, the tavern’s walls sheltered another fight for freedom, serving as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Vacant since the 1950s, divided by the construction of Rt 78, this National and State Historic Register landmark still stands, a weathered sentinel of the liberty it once helped to win. Being a historical beacon for the Minutemen, this tavern is turning on the lights again. A microbrewery and colonial museum will let the tavern live on as part of an important part of Hunterdon County’s history.

The tavern served as a meeting ground for the Hunterdon County 2nd Regiment, but also was positioned on critical supply lines to Washington’s headquarters in Morristown. All four Hunterdon County militia regiments were on duty and took part in the defense of the hills above Springfield, which became the last battle of the north. One person from the time later wrote that it looked like there were thousands of soldiers on the hills, leaving no path forward for the British without immense casualties, which led to their final retreat. June 23, 1780 brought chaos and fury with the entire village burned down. Another church of Rev. Caldwell made to ash, but not without a fight, standing their ground. Taylor’s 3rd Hunterdon Co. militia regiment brought one of the few cannons used against the British who had many. Free black militia soldier Jacob Francis also took part in the ‘Battle of Springfield’, with little records left. Another forgotten no more.

The trail in one way even extends to the Delaware river, as one of the satellite historical markers from Bonnell Tavern, tells the story about the 1776 Christmas crossing, “The Crucial 10 Days“, and how Hunterdon County aided Washington’s request.

From here, the trail of aid stretched back eastward—supporting the defenders at Springfield, Morristown, and beyond. This was the silent lifeline that made victory possible.

Forgotten Victory Trail- starting at (1) Elizabeth Point to (7) the Bonnell Tavern in Clinton

A Web of Brotherhood and Defiance

From Elizabeth to Clinton, the Forgotten Victory Trail tells more than just a sequence of battles in small local areas—it reveals a Statewide network, and boldly establishes the ‘Forgotten Chapter‘ of the American Revolution back in the annals of the origins of America. For 245 years the stories have been left in the archives, untouched and a vast majority have never even heard of critical aspects to the war in New Jersey, where Washington and his Army spent the most time fighting to save the free state of New Jersey from the Royalist British. Presbyterian meetinghouses doubled as war councils. Taverns served as both public houses and covert headquarters. Masonic lodges and Sons of Liberty gatherings bridged county lines and built trust in an age of spies and saboteurs. This is the backbone of the revolution.

In every town along the trail, ordinary New Jerseyans risked everything for the cause of independence… and it all happened here.

Forgotten Victory Trail- (1) Elizabeth, (2) Union, (3) Springfield, (4) Millburn, (5) Morristown, (6) Pluckemin, and (7) Clinton

Exploring the Forgotten State History – Walking the Trail Today

These sites are not distant relics—some are still with us, often hidden in plain sight. We are continuing to work with each municipality, historical society, and others interested in New Jersey and American history to help us build the state trail, which unites small local communities as one people across the state, and one people across the nation. This is our history.

The Forgotten Victory Trail’s historical markers (more , exhibits, and programs invite you to stand where ‘rebel’ patriots stood, to hear the echoes of musket fire, and to feel the urgency of their cause, which was a liberty that Rev. Caldwell and Thomas Paine believed in. This trail showcases the forgotten heroes, places, and people who created New Jersey and the spirit which grew into the United States, with many leading people having a hand in the creation of a world that despite its setbacks, continues to strive for the good of the people.

The Revolution is not over—it lives on in the fields, streets, and hearts of New Jersey.