The storm broke with wind, fire, and thunder. Lightning flashed over the slain as the British fled in disgrace. The murder of Hannah Caldwell ignited a hornet’s nest—Presbyterian rebels, local militias, and Continental troops rose in defiance. Towns burned. Churches and courts lay in ruin. But New Jersey did not fall. The British withdrew north, defeated and humiliated, marching toward their final loss in the southern colonies. The war here was over—but the spirit of rebellion burned brighter than ever.

On June 18, 1778, the British abandoned Philadelphia—the first capital of the fledgling nation. What followed was a string of fierce engagements, including the brutal Battle of Monmouth on June 28th. Meanwhile, Staten Island and New York City became strongholds of British power, headquarters of the Crown until the war’s end in 1783.

Across the river, New Jersey stood defiant. The towns of Elizabethtown, Connecticut Farms (now Union), and Springfield were reduced to ashes, their churches and homes burned—yet their spirit endured. This region, once home to the Old Academy (which would become the College of New Jersey, later Princeton), pulsed with revolutionary thought, courage, and unity.

Beside Rev. James Caldwell’s church in Elizabethtown stood the Old Academy—birthplace of Princeton University. There, Caldwell studied under ‘New Lights’ and Rev. John Witherspoon, who was on the board of war, which put Caldwell in the middle as a reverend upholding an idea of freedom- a Liberty Thomas Paine also believed in.

From that circle emerged the minds that lit New Jersey’s revolutionary fire. Thomas Paine, another New Jersey rebel, declared in an early draft of the Declaration of Independence- an end to King George III’s transatlantic slave trade—an indictment later removed by slaveholding southern delegates whom Jefferson appeased. Governor William Livingston condemned slavery too, though his words were ignored by his legislature.

Printers like Shepard Kollock of Chatham spread radical ideas through the New Jersey Journal, while ‘New Light’ Presbyterian ministers preached liberty from the pulpit. They were poets of freedom, heirs to a lost Renaissance—and for that, the Crown marked them for destruction. They were aligned with the original independent settlers and envisioned a world without kings and chains. Their towns were burned. Many died. But their vision of a free world endured. This lost chapter in the Origin of America, is forgotten no more.

The winter of 1779–1780 was the harshest in memory—blizzards buried the land under 6 to 10 feet of snow, and the Hudson River froze solid, strong enough to haul cannons across its ice.

Then came May 19, 1780—The Dark Day. No sun, no moon, only black skies. To many, it was Providence speaking. When Rev. Caldwell’s wife, Hannah, was murdered in her home, a violent thunderstorm followed—an omen, it seemed, to end the bloodshed.

Even across the sea, the world trembled. In London, rioters burned Newgate Prison and nearly brought down the Bank of England. It was a year when nature, war, and spirit all collided. And anything felt possible.

On June 7, 1780, British and Hessian forces launched a brutal invasion. For three hours, rebel militiamen fought to defend their homes in Connecticut Farms, even pushing the British back. From the heights of South Mountain, Rev. James Caldwell stood with General Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette, watching the fires consume his town.

He believed his parsonage—and his family—were safe. He was wrong.

His wife, Hannah, was shot and killed in her own home, by a British ‘Red Coat’. Yet Caldwell’s grief only deepened his resolve. Two weeks later, as the enemy returned, he led the local militia through the ashes of Connecticut Farms to stand again at Springfield—defending Hobart Gap, the gateway through the Watchung Mountains toward Washington’s army in Morristown.

After the smoke cleared, Washington and Lafayette departed. …but for New Jersey’s rebels, the war was over. Their land was scorched, but their spirit unbroken.

The Royal British and German Hessian invaders marched in with nearly 5,000 men and a dozen cannons. The rebels—militia and Continentals combined—numbered barely 2,000, with only a single cannon between them…but it was not numbers that won the day.

It was spirit.

They burned the village, but they could not extinguish the light carried.

The murder of Hannah Ogden Caldwell shattered the illusion of safety and lit a fire across the state. Her death—so brutal, so personal—stirred the people into a storm of unity and resistance. Around the Watchung Gap, neighbors became fighters, bound by grief and a common cause. United in liberty.

Even British General Knyphausen later admitted surprise: he expected loyal subjects. What he found instead were rebels—resolute, outraged, and unwilling to kneel.

New Jersey was the “Crossroads of the Revolution”—and every path was watched by spies wrong and right.

To the east, the Royal British Empire held New York and Staten Island, their warships lining the coast. To the west, General Washington’s army waited in Morristown, high above the Watchung Hills, guarding the gap—the narrow passage through the mountains above Springfield.

Spies moved silently across Newark, Elizabeth, Staten Island as well as in the countryside. Rebel intelligence, rooted in Hunterdon County, helped turn the tide of the war—including the daring Christmas assault at Trenton in 1776, which was aided by rebel militiamen and German Lutheran spies.

By 1780, the British returned in force- but the ground beneath them had changed. The people of New Jersey had seen too much, lost too much. The final northern clash was coming—and the rebels were ready.

New Jersey was a web of families, farms, and trade. Many were connected across counties—by kinship, by commerce, and by cause. In Springfield, prosperous mills lined the waterways, feeding local industry. Orchards bloomed. Simple white steeples with a bells and weather veins stood at the heart of it all.

It was all set ablaze.

Homes, fields, businesses, and the town’s church—burned by the enemy in a campaign of terror.

Governor William Livingston, who moved between Hunterdon and Essex (now Union) Counties, called the militia to defend something greater than land: the idea of a new nation. One of America’s earliest symbols was a half-built pyramid—unfinished, full of possibility. That was New Jersey in 1780: scarred, but building something eternal.

General George Washington made Morristown his winter headquarters—twice. In 1776, he stayed at Arnold’s Tavern in the heart of town. By 1780, he had moved to the Ford family home. Jacob Ford Sr., the home’s patriarch, had died shortly after fighting in the so-called “First Battle of Springfield”, December 17th, 1776.

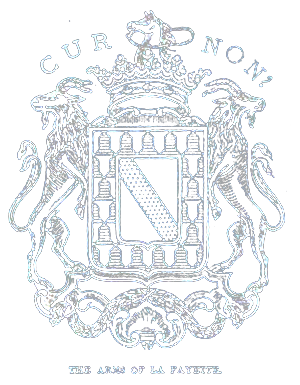

In May 1780, the young Marquis de Lafayette arrived with urgent news: the French fleet, under Comte de Rochambeau, was sailing to aid the American cause. Lafayette and Washington—bonded like father and son—rode together to the heights of Springfield during the Battle of Connecticut Farms. The path from Morristown to the end of the Watchung, let out in Springfield where the Gen. would often be seen at Bryant’s tavern, which held important military meetings.

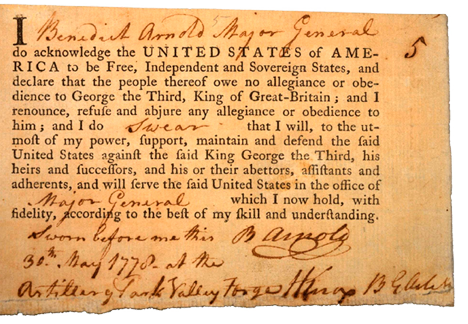

Washington’s attention soon shifted north, moving to guard West Point after discovering Benedict Arnold’s treasonous plan to hand it over to the British. That unfolding betrayal—and Washington’s swift response—unsettled British strategy, helping to stall any continued invasion at Springfield. The tide was turning, and New Jersey was at the heart of it.

The winter of 1779–1780 was merciless—twenty-six blizzards buried the roads, cutting off supply lines from western farms and gristmills in Hunterdon County. At Jockey Hollow, thousands of Continental soldiers endured conditions even harsher than Valley Forge.

Shoeless men marched through snow, starving and freezing, some reduced to chewing tree bark as smallpox swept through Morristown. Many hadn’t been paid in months. Their own farms languished without them. Young men everyone knew were dead. The Continental currency was collapsing. Winning a revolution was not certain. Despair was heavy in the air.

British intelligence whispered of mutiny, which was multiplied by Gen. Tryon and William Franklin’s Royalist-Loyalist spy network for reason to attack. Surely, some thought, New Jersey would bend to the Crown.

They were wrong.

Instead, they found a hornet’s nest of defiance. Even starving, the soldiers held their ground—unwilling to trade liberty for comfort. It didn’t matter to Gen. Tryon and Gen. Simcoe and his Queen Rangers. They were there to ensure destruction of the “Presbyterian Rebellion”, which they did but not in spirit.

West of Morristown, the farms of old West Jersey—Hunterdon County—kept Washington’s Army alive. But in the “Worst Winter,” after 26 blizzards, the roads were buried, and food, clothing, and hay for warmth vanished.

Yet from these frozen hills came defiance.

Hunterdon County was more than farmland. It was a hive of rebel activity.

It was here that Washington’s New Jersey spy network found a base. And it was from here that the bold plan to cross the Delaware and strike Trenton on Christmas 1776 was born—winning the Revolution’s first major battle.

By 1780, many who had fought at Trenton marched east again—this time to defend Elizabethtown, Connecticut Farms, and Springfield from invasion. Trenton, then still part of Hunterdon County, was the seat of a vast western region which was interconnected with groups on the east.

General Maxwell, General Dickinson, Quartermaster Charles Stewart, Capt. Beavers, Col. Abraham Bonnell of the 2nd Regiment, and Col. Taylor—whose gristmill fed starving troops at Jockey Hollow—all answered the call. The 3rd Regiment of Hunterdon County joined them, with men like free African American Jacob Francis. These were not professional soldiers. They were farmers, craftsmen, and rebels of all kinds—Minutemen, ready to defend an idea. Not all ideas were won, but the sparks were started by some good ones.

Global Rebellion, Secret Alliances

Lafayette, Arnold, and the Turning of the Tide

As the Battle of Springfield loomed, Benedict Arnold’s betrayal nearly changed everything. His secret letters to British spy John André—signed “Mr. Moore”—were discovered, warning General Clinton to march north and sever the rebels from the arriving French. But it was too late.

Atop the hills of Springfield, General Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette—just 22, descended from the French Knights Templar—stood together. Enlightenment ideals burned in Lafayette’s heart, fanned by thinkers like Thomas Paine, printer Shepard Kollock, and symbolist Francis Hopkinson—designer of America’s first flag, with its six-pointed stars for a new constellation of states not colonies.

The Revolution had become global. France sent ships, gold, and men. Spain, the Netherlands, and rebel Scots and Irish joined the cause. Baron von Steuben, a Prussian noble, drilled Washington’s ragged troops into a fighting force. Pulaski, Kościuszko, and others rallied to liberty’s banner. Scottish Gen Knox setup America’s first military academy and artillery cantonment in Pluckemin. Even Dutch Patriots sent secret loans and privateers to harass the Crown.

What began as civil war in 1776 had, by 1780, become a forgotten world war for freedom.

We are closely allied with the Washington Association. Members of the Washington Association of New Jersey demonstrate their commitment to increasing the public’s awareness of the history in New Jersey and is a vital link in our collective history and an irreplaceable national asset. This leadership support enables us to present our research and celebrate America’s unique historical site on a larger public view.

WANJ was founded to acquire and preserve Washington’s Headquarters at the Jacob Ford Mansion. It was chartered by the New Jersey legislature in 1874 and is the not-for-profit advisory and fundraising body for the Morristown National Historical Park (MNHP). The main structure in the park is the Jacob Ford Mansion, where Washington headquartered in the winter of 1779-1780, with Washington’s departure on June 23, 1780, the Battle of Springfield.